How Small Players Gain Ground While Big Players Lose It

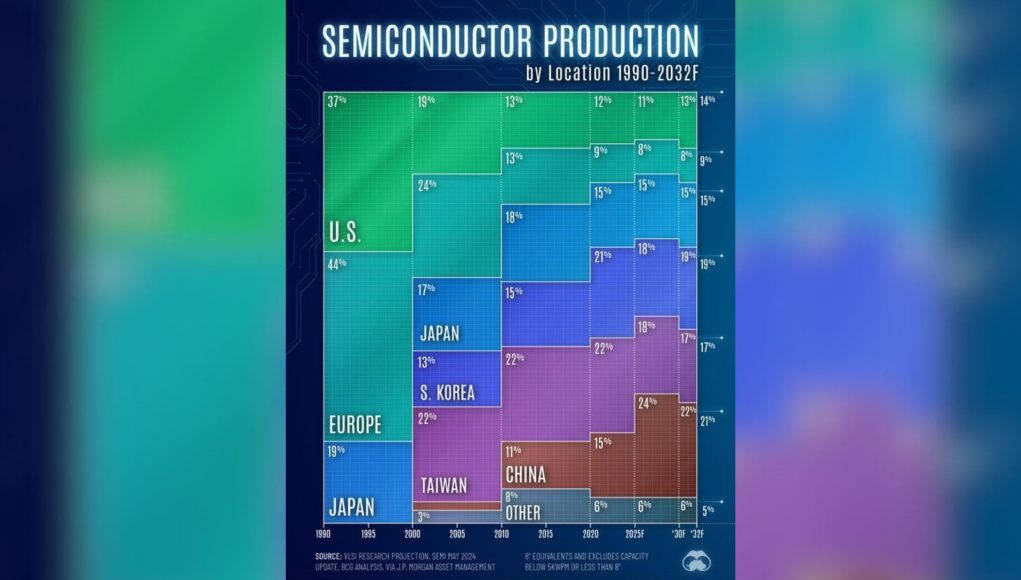

History has a way of humbling giants. Rome ruled the known world—until it didn’t. Nokia once dominated mobile phones—until it missed the smartphone revolution. The U.S. led semiconductor production—until Taiwan and South Korea surged ahead.

The cycle is familiar: big players become complacent, small players become hungry, and markets shift. But why does this happen so frequently? And what can businesses—and professionals—learn from it?

The Anatomy of Market Disruption

The semiconductor industry serves as a compelling case study of how incumbents fall and challengers rise. In 1990, the U.S. and Japan accounted for the vast majority of global semiconductor production. Today, Taiwan, South Korea, and China have taken over the lead.

This isn’t an isolated incident. The same pattern has played out in industries like automobiles (Tesla vs. legacy manufacturers), retail (Amazon vs. Sears), and entertainment (Netflix vs. Blockbuster).

So what exactly causes this shift?

1. Complacency Kills Giants

“Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.” —Bill Gates

Big players dominate markets because they are good at what they do. The problem? They get too comfortable doing the same thing.

In the semiconductor world:

- The U.S. led in the 1980s and 1990s because it pioneered the industry. However, instead of doubling down on chip manufacturing, U.S. firms focused on high-margin design work, outsourcing production to Taiwan and South Korea.

- Japan, once a powerhouse, failed to adapt to the rise of fabless semiconductor companies, where design and manufacturing were split. While it clung to integrated models, Taiwan and South Korea embraced specialization.

The lesson? Being at the top breeds inertia. Large firms build bureaucracies, prioritize short-term profits, and hesitate to disrupt their own models—giving smaller players an opening.

Example: Kodak and the Digital Camera Revolution

Kodak invented the first digital camera in 1975. But because its business depended on film sales, it refused to invest in digital technology. Instead, smaller companies like Sony, Canon, and Nikon drove the transition.

Kodak wasn’t technologically behind—it was psychologically trapped in its own success.

✅ Key Takeaway: If you’re at the top, disrupt yourself before someone else does.

2. Agility Beats Scale in Fast-Changing Markets

“It is not the strongest species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.” —Charles Darwin

Big companies often believe that size equals strength. But in fast-changing markets, size equals rigidity.

How Smaller Players Use Agility to Win

- Taiwanese and South Korean firms saw an opening in semiconductors. While Intel and Texas Instruments dominated the market in the 1990s, TSMC (Taiwan) and Samsung (South Korea) focused on contract manufacturing.

- These smaller firms were fast, efficient, and willing to experiment with new fabrication techniques.

- While U.S. firms debated whether outsourcing was wise, TSMC and Samsung perfected the art of chip manufacturing, leading to today’s dominance.

Example: Tesla vs. Traditional Automakers

For decades, Ford, GM, and Toyota ruled the car market. Then Tesla entered—small, scrappy, and willing to bet on electric vehicles when others dismissed them.

By the time legacy automakers realized the market shift, Tesla had years of experience in battery technology, software integration, and direct-to-consumer sales.

✅ Key Takeaway: In changing markets, the ability to pivot quickly is more valuable than having deep pockets.

3. Strategic Investment in Undervalued Areas

“The secret of change is to focus all of your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.” —Socrates

Smaller players look for the gaps big players ignore.

In the semiconductor industry:

- The U.S. assumed manufacturing was a commodity—not a core capability—so it focused on design and R&D.

- Taiwan and South Korea saw an opportunity in fabrication, investing heavily in world-class manufacturing facilities.

- Today, Taiwan (TSMC) and South Korea (Samsung) manufacture the world’s most advanced chips, while the U.S. is scrambling to rebuild domestic production.

Example: Netflix vs. Blockbuster

Blockbuster dominated the video rental industry. When Netflix introduced a subscription-based DVD rental model, Blockbuster laughed it off.

Then Netflix pivoted to streaming. Instead of fighting to keep DVD rentals alive, it invested in a future that Blockbuster ignored.

By the time Blockbuster tried to enter streaming, it was too late.

✅ Key Takeaway: Winning the future requires investing in what’s next, not in what’s comfortable.

4. Globalization and Government Support Tilt the Playing Field

“Economic destiny is not written in stone; it is forged by policies and investments.”

Small players often rise with strategic government support.

In semiconductors:

- Taiwan’s government invested heavily in TSMC and local tech firms, providing funding, talent pipelines, and R&D support.

- South Korea backed Samsung’s semiconductor ambitions, offering incentives to ensure its global competitiveness.

- China is aggressively pursuing self-sufficiency in semiconductors, pouring $150 billion into domestic chip production to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and Japan took a hands-off approach, assuming market forces alone would maintain their dominance. They were wrong.

Example: China’s Rise in Renewable Energy

China wasn’t always a leader in solar panels and electric vehicles. But by heavily subsidizing solar and battery manufacturers, it now controls:

- 80% of the world’s solar panel supply chain

- The largest EV battery production capacity

Western competitors, believing the market would stay the same, fell behind.

✅ Key Takeaway: A strong ecosystem—not just great products—creates long-term success.

5. The Relentless Drive of the Underdog

“Champions are not made in the gym. Champions are made from something they have deep inside them—a desire, a dream, a vision.” —Muhammad Ali

Smaller players often have an existential need to win.

For Taiwan, South Korea, and China, semiconductors are not just business—they are national priorities.

- Taiwan knew it could not compete with China in scale, so it built an unbeatable semiconductor niche.

- South Korea had no oil or natural resources—so it bet big on technology and manufacturing.

- China is determined to be self-sufficient in tech, aggressively investing to close gaps.

In contrast, U.S. semiconductor firms got comfortable. Japan’s firms relied on past successes. And that’s how they lost ground.

Example: Amazon vs. Brick-and-Mortar Retail

Amazon started as an online bookstore. It didn’t have a safety net—it had to fight to survive.

Meanwhile, retail giants like Sears, Macy’s, and Walmart assumed online sales were a side business.

Amazon relentlessly innovated, while traditional retailers hesitated. Today, Amazon is worth more than most legacy retailers combined.

✅ Key Takeaway: The hungry, ambitious, and relentless will always outwork the complacent.

Conclusion: What Can Professionals Learn from This?

Markets evolve. Industries shift. Giants fall. The same patterns apply to individual careers.

🚀 Don’t be the Blockbuster. Be the Netflix. 🚀 Don’t be the Kodak. Be the Canon. 🚀 Don’t be the U.S. semiconductor industry in 1990. Be Taiwan in 2024.

If you want to sustain your competitive advantage, focus on: ✅ Continuous learning ✅ Agility and adaptability ✅ Investing in undervalued opportunities ✅ Building an ecosystem of skills and networks ✅ Staying hungry, even when successful

The winners of tomorrow aren’t the biggest. They’re the smartest, the fastest, and the most adaptable.

So the question is: Are you adapting fast enough? 🚀